|

by Jackson Phinney

The 1984 film Amadeus is not really about Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart, or at least not directly. It is actually

about one Antonio Salieri, who worked in the late 18th century

as the court composer for Emperor Joseph II of Austria.

In the film, Salieri and Mozart wind up living, working,

and writing music in the city of Vienna at the same time

– Salieri is industrious, well respected, and reserved,

whereas Mozart is, by contrast, asinine, flippant, and chronically

immature. Salieri slaves away at his keyboard night after

night, beseeching God to visit him with musical inspiration;

Mozart pens his immortal melodies quite literally between

fart jokes.

The central tension of the film lies within the fact that

Salieri is actually a very good musician. His own abilities

allow him to recognize that Mozart is a genius, but, crucially,

are not significant enough to enable him to write genius

music himself. He is cursed with a mere morsel of Mozart’s

ability, made to look on as Mozart conjures, without the

slightest bit of effort, the most brilliant collection of

musical works ever known to man.

My relationship with the 21-year-old Philadelphia songwriter

Alex G is a little like that: He is the Mozart to my Salieri.

I love music, and I am good at making it – just good

enough to realize that Alex G, a prolific and little known

bedroom-recording artist the same age as myself, is possessed

of a talent so immense that I am almost

comfortable labeling him a prodigy. While his music may

sound like Built to Spill or Big Star, in my eyes he has

more in common with Franz Liszt or Beethoven.

I realize that I sound insane making such comparisons, but

to describe Alex otherwise would be to sell him short. From

my vantage point, as a hardworking artist and a passionate

fan of music, Alex appears to belong to a class of musicians

so select as to encompass practically no one else working

in indie today. His approach is so seemingly effortless,

his command of melody so intrinsic, his style so distinctive

that I am left grabbing hopelessly at hyperbolic straws

even attempting to describe his work, much less create something

equal to it.

His most recent run of records (2012’s watershed

Trick and Rules, 2013’s brilliant split 7”

with Los Angeles songstress R.L. Kelly, and his newest full-length,

DSU) are bafflingly good. Trick and DSU

in particular are so jaw-droppingly excellent that, from

my perspective as a songwriter, Alex appears to be playing

by fundamentally different rules than the rest of us. And

indeed, perhaps he is.

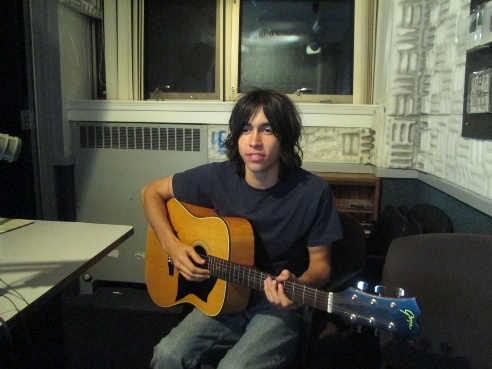

Alex himself, as was mentioned above, is a 21-year-old kid

from Philadelphia - his full name is Alex Giannascoli. He

is a rising senior at Temple University, and studies English.

Until recently he sported a head of straight, greasy, shoulder-length

black hair, which was perhaps the most notable aspect of

his appearance. He dresses simply, speaks infrequently,

and seems totally unconcerned with appearing “cool”

or “hip” in any capacity. If the adolescent

Severus Snape had bagged groceries or worked a summer gig

at Blockbuster, he might have made a similar impression

upon the general populous, which is to say, an unremarkable

one.

I first saw Alex in person at one of his shows in Brooklyn

a month ago; in the time leading up to his set he meandered

around the venue in a pair of jeans and a baggy red hoodie

which most style-conscious New Yorkers would not be caught

dead in. He moved from one back corner of the room to another,

slouched, nursing a PBR, speaking occasionally to friends

with a glazed look in his eyes and a semi-stoned grin on

his long, boyish face. When I got up the courage to speak

to him (at this point I had been obsessing over his music

for half a year, almost completely eschewing all other stimulation

in favor of his 2012 album Trick during that time) I might

as well have been ordering McDonalds at a drive-thru window.

Every remark I made and every superlative I offered seemed

to register only faintly, as if the Alex I was currently

speaking with was merely taking a message for the Alex I

had come to know through the music.

“Ah, yeah, thanks, man, cool, shit.” The same

cryptic smile, the same warm and yet totally unreadable

expression, and the same distinctive feeling that I was

trying to talk to someone at the other end of a long tunnel,

in a blizzard, with the lights off, in a language that they

did not fully understand.

I mention all of this to underscore the jarring gap between

Alex Giannascoli, the young and slightly catatonic college

student, and Alex G, the best and most fascinating songwriter

currently active. When Alex finally took the stage that

night in Brooklyn, he (and his excellent band, who play

with him live but not on his recordings) casually dished

out perhaps the most stunning half-hour of live music that

I have ever been party to. Watching Alex play was like finding

a fist-sized diamond inside of a bag of Cheetoes, as song

after laughably perfect song burst out of this kid who seemed

absolutely, almost perversely, ordinary.

However, anyone who has ever visited Alex’s Bandcamp

page knows that this impression of contrast extends well

beyond his live set, and is indeed a crucial part of his

appeal. The site that hosts his music is, like the man himself,

almost aggressively uncool: it sports a featureless black

banner and a plain navy background, upon which are displayed

12 of the worst album covers I have ever seen. Indeed it

was at this point that, after Alex’s music was first

recommended to me over a year ago, I made a swift about-face

without listening to so much as a single song: the site,

like Alex, seemed categorically incapable of containing

the brilliant music which it was purported to. Indeed, even

now the Bandcamp is shocking to me – the gorgeous,

electronically tinged single “Lucy” is represented

by a blurry picture of a dog and a slipper, with the title

slapped across the top in the unmistakable hand of Microsoft

Paint. The 2011 single “Good,” which not only

sounds like Elliott Smith but is at least as good as any

of that songwriter’s best material, features a confounding

photo of Alex in a backwards raccoon-skin cap and cheap

sunglasses, with the tail acting as a sort of snout. The

list of strange grievances goes on (the cover of “Joy”

even features a typo), and one would be forgiven for not

wanting to listen to any of these albums. But the more I

fall in love with Alex’s music, the more I realize

that these oddities are part of the basic makeup of his

genius.

Alex does not need to look cool, or have a sleek website

with tasteful album art, because the better part of his

output since 2011 represents the strongest debut showing

by a songwriter since the turn of the millennium. Not all

of it is at this level, as Alex is extremely prolific and

his (relatively speaking) “less mature” work

(which is to say, the stuff he made when he was 17 and 18,

and perhaps even younger) suffers naturally from a lack

of focus. However, his best material (some of which was

indeed created at these young ages) is so good as to be

almost unbelievable. In my opinion, in Alex G we are witnessing

the birth of a first-rate talent, the likes of which the

traditional modes of “rock” and “indie”

songwriting have been missing for a very, very long time.

I am loath to say these things because the current hype-mongering

which is engaged in to try and drum up interest for artists

in our oversaturated musical climate is effectively killing

indie (or already has.) But in this particular case, I ultimately

don’t care. Alex is, unlike so many others, the real

McCoy: The genuine article. Like Brian Wilson, early Bob

Dylan, and ‘70s Neil Young, it feels inadequate to

describe Alex as an “artist,” in the traditional,

pedestrian sense of the term; to me, he feels closer to

a visionary. As with Dylan and Young, Alex’s best

work is so varied and so excellent that it becomes effectively

impossible to imagine a single person being responsible

for it all. From an outside perspective, it seems to me

that Alex is acting as a sort of conduit for exceptional

musical ideas; it is as if he has one foot in our world

and the other in a realm utterly inaccessible to must of

us. To further this impression, a recent interview with

Alex noted that he “has trouble articulating certain

details of his creative process, often second-guessing his

responses and fumbling to answer questions… When [asked]

about influences, he goes blank.” To me, this is unsurprising

– Alex’s music is so good that I cannot imagine

him consciously endeavoring to create it. It seems to come

from beyond him, almost as if he were possessed by something

larger than himself; the music seems to pass through him,

rather than originating within him. It is fascinating and,

as a musician, profoundly humbling.

I realize that, for those unfamiliar with his work, I have

done little more here than place Alex on an enormously high

pedestal. While I have felt this way about Alex for many

months I have been, up until now, reluctant to do precisely

that. This week, however, changes things; as of Tuesday,

Alex’s new full-length ‘DSU’ has been

made available for streaming and pay-what-you-will download.

It is an absolutely exceptional record in its own right,

and for me personally its readily-accessible existence is

a cause for some relief. This is because, prior to ‘DSU,’

one of the biggest issues with Alex was that, for some unfathomable

reason, he was failing (or choosing not) to release large

quantities of his best music. While Alex’s official

Bandcamp features some dozen releases, his best collection

of songs is, inexplicably, not amongst them; for this reason

I believe that many tentative converts to his music end

up missing out on what is undoubtedly his best stuff. ‘DSU’

secures another excellent 13 songs safely within his Bandcamp

and will prove an excellent starter-kit for new fans –

but for those who desire more, it will require a little

internet spelunking to unearth the set of tracks which,

combined, stand as the best “album” of the last

few years.

When I discovered Alex’s music, I began on his site

with ‘Trick,’ which had been (rightfully) recommended

to me. That record exploded inside of my music-centric life

like a Peep in a microwave - I could not believe how good

it was. From the opening guitar murmurs of “Memory”

I was spellbound by the strange mix of warped melodicism

and cryptic, even nonsensical poetry. The opening lines

continue to haunt me frequently throughout my day:z

“I was waitin’ for a baggie / A powder

bunny / I have a buddy I grew up with / He hooked it up

for me.”

While I doubt if anyone besides Alex (and perhaps not even

him) has any idea what this means, it does serve to highlight

one of the most compelling qualities about his music, which

I think frequently drives fans to obsession and is probably

responsible for his current status as a “cult”

artist. This is that there is something intrinsically odd

about Alex and his music, and the more one familiarizes

oneself with it all, the more it seems as if the entire

package was being beamed in from some slightly different

world. The demented, childish album covers (‘Trick’

features a German shepherd running down the center aisle

of a church, with the title of the record in a ghastly teal

font above the altar), the relentless output of music, which

itself feels strangely anonymous, and above all the lyrics,

which often traffic in commonplace themes but in such a

way that everything feels somehow off (“My favorite

animal / Is the whale / I like his big fat tail. / I wanna

cut off a piece of him / And I’ll share / You get

a piece of the whale.”) Even the song titles fit this

bill: almost always comprised of a single word, the tracklists

of his albums wind up reading like word-association shopping

lists compiled by aliens attempting to successfully assimilate

into human society (1. Memory, 2. Forever, 3. Animals, 4.

String, 5. Advice, 6. People…) All of this, combined

with Alex’s person and even the basic information

available about him (his artist photo on Bandcamp is a rough

sketch of a bony, galloping horse, and the only personal

information included is the curious email address “monsterhead7@aol.com”)

suffices to surround the man and his work in an aura which

is equal parts unknowable auteur and peculiar, enchanted

wunderkind.

This impression only deepens the further one progresses

into Alex’s world, and the more time one spends there,

the more irresistible the whole thing becomes. On stage,

for instance, Alex stands, legs apart, swaying robotically

side to side like an absentminded cuckoo clock, with his

tongue often dangling from his mouth and a bemused, vacant

expression plastered on his face. It is, from personal experience,

both extremely weird and absolutely captivating. There is

a drive to understand this person, who offers so much of

himself in his music and yet remains always, inexplicably,

tantalizingly, unknowable.

While ‘Trick’ served as my gateway into this

strange fascination, I was soon in need of more –

as much as I could possibly get my hands on, to be exact.

‘Trick’ is a watershed, a tour de force of Alex’s

preoccupations (childhood, aging, the difficulties arrived

at when the two begin to coincide). It also plays as a showcase

of his influences, unconscious or otherwise (Built to Spill

and Big Star seem the obvious touchstones, with spidery

guitar riffs and totally effortless melodicism constantly

in the foreground, but the specter of Elliott Smith is also

often present, particularly on tracks like (the heartbreaking,

impossibly poignant) “Change”). Given ‘Trick’’s

scope, it is the perfect place to begin – but immediately

beyond its 13 tracks, things become slightly more difficult.

Alex’s other releases are not as consistent, although

each features at least a handful of songs so excellent that

one cannot risk skipping over the record entirely. ‘Rules’

is, after ‘Trick’, the one with the highest

batting average – indeed, the more time I spend with

it the more I realize that it is essentially a masterpiece

in its own right, more subdued and less sprawling than ‘Trick’,

but also more personal and a bit less eclectic. ‘Easy’,

a collection of seven songs from 2011 (“didn’t

really have time to finish” reads the laconic description

beneath it on Bandcamp (the most information offered about

any release)) features a few through-the-stratosphere incredible

moments, particularly the uncharacteristically verbose “I

Wait For You.” ‘Race’ includes “Gnaw,”

a love-song / reminiscence hybrid which could easily go

toe to toe with any randomly chosen all-time indie classic

– Pavement’s “Gold Soundz,” for

instance. The aforementioned untitled split 7” with

R.L. Kelly features three of his best pieces, in particular

“Magic Mirror” which, in less than 90 seconds,

proceeds to hollow the listener out completely.

The list goes on, and the more time one spends parsing through

this thick back catalog, the more rewarding it proves. Prior

to ‘DSU’, however, Alex’s best stuff existed

only on YouTube, posted by a handful of users who seem to

have access to a large swath of his music which he himself

has chosen not to share in an official capacity. The YouTube

user ‘Keyan28’ has posted a dozen or so excellent

rarities, all of which really ought to be compiled and sequenced

somewhere more prominent given how mind-bendingly excellent

they are. “Sarah” is one such track, a masterpiece

of Brian Wilson/Bach level counterpoint which is, for my

money, the best thing Alex has ever done – my entire

face slackens every time I listen to it, and the fact that

it has less than 3,000 views is a crime against humanity.

“Kara” is similarly great, a quiet, shambling

number that progresses through a series of impossibly perfect

little harmonic turns; “Break” is analogous

in tone and just as good – again, the list simply

goes on. Other equally essential moments are to be found

elsewhere; “Be Kind” exists only as a video

of Alex playing it alone in an abandoned stairwell, “Nintendo

64” on a random YouTube account with only the faintest

apparent connection to Alex, and so on. To be an Alex G

fan, then, is to indulge in a bit of obscurism, and truly

this is part of the fun – the joy of stumbling across

a new song, only to realize, yet again, that it is actually

one of the best things I have ever heard has been an endlessly

enjoyable enterprise over the last few months, and the more

time I spend doing this, the more Alex’s entire existence

feels like some kind of incredible, inexplicable gift to

fans of “indie music” in general, whatever that

tired term may mean in such a new and exciting context.

Now, of course, we have DSU, and it will be easier

to introduce people to Alex’s music because of it –

here, as with ‘Trick’, we have an album which

collects all of Alex’s disparate strengths and offers

them in a readily digestible package. Unlike ‘Trick’,

however, DSU does not simply sum up what Alex is

good at – it pushes his sound into uncharted territories,

and as such prior fans of his music will find it simultaneously

familiar and challenging. On the whole, DSU may even

be better than ‘Trick’, which I never imagined

myself saying – the expectations that I brought to this

album were unfair in the extreme, and Alex responded by offering

a collection of songs that obliterated such preconceptions

as a matter of course. It is a masterpiece of a record –

totally schizoid in terms of style, veering happily between

pop immediacy and a sort of mid-fi psychedelia, at once approachable

and esoteric: I cannot imagine a better showing for Alex’s

first outing on something approaching a “center stage.”

For in many ways, DSU feels like a debut for Alex,

or at least a showcase of heretofore-unprecedented stature.

For one, it is his first release with the rising Brooklyn

label Orchid Tapes, a loose collective of musicians who are

arguably producing the best and most exciting music in the

entirety of Indiedom at the moment. The label, home to the

likes of Sam Ray (Teen Suicide, Julia Brown, Ricky Eat Acid)

and Mat Cothran (Coma Cinema, Elvis Depressedly) has proven

itself over the last few years to be a bright light in the

otherwise dreary landscape of independent music. Through word

of mouth, organic snowballing of hype (as opposed to the top-down

manufacturing of hype which seems all-pervasive in the upper

echelons of indie) and a roster of uncommonly talented songwriters

and musicians, Orchid Tapes are rightfully posed to become

a Big Deal in the near future – as such, it makes sense

that Alex has signed with them. Both Orchid Tapes and Alex

G have built their reputation upon little more than putting

their money where their mouths are – no corporate interests,

PR firms, trendy management, or payouts have been involved

in establishing them as new and exciting entities. They have

simply worked hard, and garnered a formidable host of fiercely

loyal acolytes. In a current musical climate where our attention

drifts from one artist to the next on a daily basis, in accordance

with what one or two trendmaking websites has deemed worthy

of our ears, this type of ground-up structuring is in short

supply and, as a function of such scarcity, proves extremely

refreshing.

Thus, DSU’’s release through Orchid Tapes

feels like an Event for a host of reasons. The people devoted

to this artist and to this label are exactly that –

devoted, to the core, of their own accord. The press DSU

has received this week (highly positive reviews from Pitchfork,

Rolling

Stone, and Consequence

of Sound, amongst others) feels like a serious victory,

a sort of coup staged on the hulking monstrosity of the music

blogosphere by a small group of people who have made it happen

through a mixture of elbow grease and serious talent. DSU

is only the label’s third vinyl release, and the first

pressing of 250 records sold out in a number of hours. The

second went almost as fast, the third is selling well, and

the cassettes were gone instantly. While both Orchid Tapes

and Alex G are relatively small enterprises, this release

in particular feels like the biggest moment for each of them,

and for myself, an ardent fan of both, it feels like the most

exciting moment in music since the beginning of this decade.

None of this would be worth mentioning, obviously, if DSU

wasn’t almost comically good. I knew Alex was extremely

talented, but I must confess, I did not know he had something

like this in him. The album retains, and even serves to amplify,

Alex’s two core strengths: his first-class songwriting,

and his intrinsic weirdness. New and old influences can be

glimpsed in the kaleidoscope of this thing – the percussive,

harmonic laden guitar-playing characteristic of Modest Mouse’s

Isaac Brock (“Axesteel”), the hypnotic, krautrock-flavored

instrumentation of mid-period Deerhunter (“Serpent Is

Lord”), the warped, childlike pop-immediacy of Guided

By Voices (“Harvey”). But, as with all great albums,

Alex weaves these preoccupations into a tapestry that is unmistakably

his. To some extent, DSU reminds me of Deerhunter’s

2010 album ‘Halcyon Digest’, insofar as each record

feels a bit like flipping through an old record catalog while

on acid. In this vein, DSU is not a coherent listen,

and this is part of its appeal upon repeat listens. Each song

feels like a perfect little diorama set in an alternate universe

– all of them include recognizable elements, but they

are presented in such a way that they seem to belong to Alex

alone, to originate with him, within his world. It is nothing

short of breathtaking.

The enhanced production (and mastering, which is a first for

Alex) also helps enormously. What were once rough sketches

are now vivid realities, and just as Alex’s songwriting

often feels as if it has its roots in a place unknown to most

of us, so too with the textural choices he has made on this

album. The creepy, bit-crushed pitch-shifting of his own unaffected

voice is particularly effective, as are the woodwind-esque

synth textures, which are something of a trademark for him,

but which are here processed in a new way. The sonic landscape

of each track differs massively from one to the next, and

the sequencing of the album is not conducive to a holistic

experience. But all of this is in service of Alex’s

greater vision, as the album bucks and revolves like some

kind of extra-dimensional roller coaster ride. The sky-screaming

charge of opener “After Ur Gone” leads into the

snarling, discordant churn of “Serpent Is Lord”;

the doll-house creepiness of “Black Hair” gives

way to the gliding, acousmatic riffs of “Skipper.”

The record culminates with some of its strongest material,

the surprisingly lucid and immediate “Boy,” and

the record’s centerpiece, “Hollow.” The

latter is exceptional even for Alex, a four-minute, slow burning

confessional that threatens to completely break your heart

every time it is played. It is an absolute showstopper, replete

with wind chimes and Justin Vernon-esque choral harmonies

– to me, it feels like the autumn wind blowing through

my hair on a walk home alone at night. It is otherworldly;

I cannot think of another song as good as “Hollow.”

On the whole DSU is, then, everything Alex’s

small group of fervent fans could have possibly hoped it

would be, and with it a set of interesting questions for

Alex and for his label are set into motion. Alex Giannascoli,

for all intents and purposes, remains a peculiar and idiosyncratic

college student who just happens to have the best musical

mind of anyone under 30. He hardly promotes, he apparently

does not care about how he is received, or even if people

hear his best music which, I assert, is the best stuff that

has come out, bar none, in the last 15 years. The implications

of this are fascinating – does Alex G point towards

the next step for indie rock? We constantly hear how bored

everyone is with Pitchfork & co. and their stultifying

monopoly over what is designated as “cool” –

but Alex has done this without them, or anyone like them;

in truth, Alex has done this practically alone. People simply

love Alex’s music – they trade it, they discuss

it, they purchase it and come to see it live without being

told to by any sort of tastemaker. And he is really making

progress – in New York, at least, I have been hearing

about him nonstop this summer, and almost always in a favorable

capacity. The Brooklyn show I saw him at was positively

electric; when Alex got on stage, I got the same feeling

in my stomach that I get from watching live Bob Dylan footage

from the mid-1960’s – the feeling that the man

on stage is better at what he does than anyone else in the

world. When I looked around the room, I could tell that

I was not alone.

Alex is becoming a big deal, in a way that people aren’t

supposed to become big deals anymore – organically.

And what’s more, his label is along for the ride.

The two are growing in tandem, as artists like Alex, the

aforementioned Sam Ray and Mat Cothran, and other excellent

signees like Infinity Crush and R.L. Kelly hit their stride

simultaneously, engendering a very real feeling that the

sky is the limit on this thing. In watching this unfold

over the last year, I have felt increasingly that the flowering

of this entire scene is serving to subvert many of the negative

aspects of the independent music world at large. Here, a

group of uncommonly talented artists has gotten together

and pushed each other collectively to be the best that they

can be; they have built this thing themselves, promoted

it themselves, kept it afloat themselves, and made money

off of it themselves. They have remained outsiders and,

in so doing, their success feels real and exciting in a

way that almost nothing does anymore. Those who support

them feel like a part of their family because they are a

part of their family – by organic it is meant that

everyone takes part. In many ways the spirit of community

has been lost in indie over recent years – while we

all visit the same websites and listen to the same artists,

we do it because we are told to and we do it without really

communicating with one another. Orchid Tapes stands in opposition

to this, and certainly the very existence of Alex G stands

in opposition to this.

We keep hearing that traditional, “guitar based”

indie music is dead – but when faced with an artist

as good as Alex, one is forced to admit that this simply

is not true. He is so good and so exciting that it feels,

on the contrary, alive and well. We keep hearing that the

internet-based indie music distributing/consumption machine

is broken – but with a label like Orchid Tapes, who

utilize the Internet in a new way, such a concern feels

similarly absurd, and even outdated. We hear that the traditional

album release cycle is no longer effective – but Alex

and Orchid Tapes release music in a new way that is effective.

We hear that money needs to be poured into an artist before

they can be picked up by the proper channels – but

artists like Alex and labels like Orchid Tapes work without

that money through different channels. In light of all of

this, then, one can glimpse the first hopeful stirrings

of a paradigm shift in the way that indie music is discovered

and consumed. The dull era which we find ourselves in may

yet prove to be a slouch and not an end, and perhaps, simply

by virtue of how stupidly, unthinkably, preposterously good

he is, Alex will show us the way out.

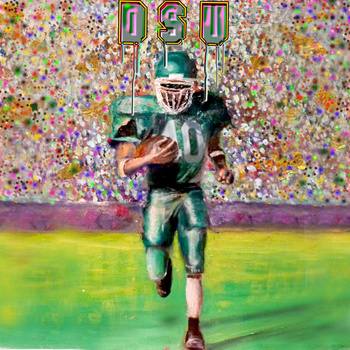

The cover of DSU features a painting of a football

player, in mid-stride, running down the field. The ball

is tucked beneath his arm, and there is not another player

in sight – it looks like he is running for a touchdown.

When I look at it, I imagine Alex Giannascoli underneath

the helmet.

Check out Alex G’s music at http://sandy.bandcamp.com/

JerseyBeat.com

is an independently published music fanzine

covering punk, alternative, ska, techno and garage

music, focusing on New Jersey and the Tri-State

area. For the past 30 years, the Jersey Beat music

fanzine has been the authority on the latest upcoming

bands and a resource for all those interested in

rock and roll.

|

|

|