by Paul Silver

In the 1980s, Washington, DC was the big thing in the punk

and indie music scene, with Dischord Records putting out

influential hardcore releases from bands like Minor Threat.

That scene evolved, and was instrumental in creating the

genre that’s known as emo. Huge bands like Bad Brains

and Fugazi came out of that scene. Meanwhile, scenes in

Athens, GA and Chapel Hill, NC were producing bands like

REM, Neutral Milk Hotel, Of Montreal, Flat Duo Jets, Superchunk,

and Archers of Loaf, and the influential Merge Records was

born. On the other side of the country, Seattle exploded

with the grunge sound, with Sub-Pop Records rising rapidly

on the backs of bands like Nirvana, and local acts such

as Soundgarden and Pearl Jam went on to national prominence.

Meanwhile,

in San Diego, things were also brewing in indie music. Out

of the violent southern California hardcore punk scene of

the early 80s, a new breed of bands was growing, maturing,

and creating unique and powerful music. The growth from

the 80s into the 90s was nothing short of astounding, and

critics and the mainstream started to take notice. Some

people, when speaking of the San Diego music scene, likened

it to these other scenes that exploded into the mainstream,

and major labels began courting these die-hard DIY musicians,

who were never very comfortable with the idea of mainstream

success. Meanwhile,

in San Diego, things were also brewing in indie music. Out

of the violent southern California hardcore punk scene of

the early 80s, a new breed of bands was growing, maturing,

and creating unique and powerful music. The growth from

the 80s into the 90s was nothing short of astounding, and

critics and the mainstream started to take notice. Some

people, when speaking of the San Diego music scene, likened

it to these other scenes that exploded into the mainstream,

and major labels began courting these die-hard DIY musicians,

who were never very comfortable with the idea of mainstream

success.

What made the San Diego scene different from these others?

And why was this prophecy of wider success never quite fulfilled?

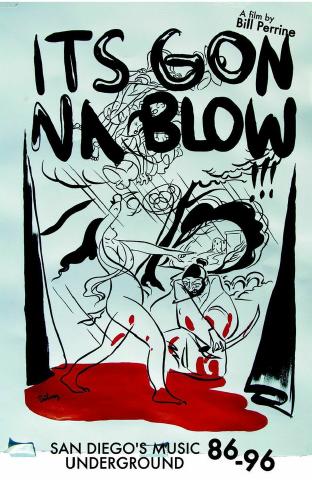

That’s the subject of a new documentary film from

Bill Perrine, entitled, “It’s Gonna Blow!!!

The San Diego Music Underground 1986-1996.”

Q: When you’re not making this film, what do you

do?

Bill Perrine: Well, I’m a director, and editor, and

occasional cameraman. Very occasional photographer. But,

I basically work, in one form or another, as a filmmaker.

You know, everything from documentaries and features to

corporate videos and boring stuff like that.

Q: And the name of your company?

BP: It’s Billingsgate Media.

Q: So tell us a little about Billingsgate Media.

BP: [Laughs] Well, Billingsgate Media is really just me.

And whoever I can convince to come along on a shoot, for

the least amount of money possible. But it comes out of,

I used to do four-tracking, back in the day. I’d record

music. And an old girlfriend used to call me Billingsgate

as a nickname. And I had the website, so when I started

doing films and things, I was too cheap to buy a new website

[laughs], so that’s how Billingsgate Media came up.

Q: How long have you been doing video production, and what

sort of work do you do?

BP: Uh, god, I’m really terrible at dates, maybe about,

six years? Something like that? What was the second part

of the question?

Q: What sort of work have you done?

BP: Well, I directed a movie called “Children of the

Stars,” which is about a UFO group out in El Cajon

(California) called Unarius, and their relationship to reality.

I’ve worked as a producer, as an editor, on a bluegrass

documentary a guy named Rick Bowman did, another film he

did about a turn-of-the-century courthouse shooting back

in the south. It’s really interesting. I’ve

worked as a DP on another music film about a classical pianist.

I’ve done all kinds of stuff. That doesn’t even

include commercials for [laughs] glass replacement companies

and other things like that.

Q: OK, so tell us a little bit about that.

BP: Oh, that’s, honestly, that’s…

Q: That’s what pays the bills.

BP: Yeah, honestly, that’s going to bore the shit

out of anybody listening to that. [laughs] But I do stuff

for non-profits. I’ve done a lot of work for local

non-profits, like the Media Arts Center, which does education

for at-risk youth, and I do low-budget internet commercials,

things like that, I mean, anything. I’ve done, god,

I don’t even know what I’ve done, everything

from, like I said, glass replacement companies to mattress

companies to doctors and vets, and Tijuana dentists. That’s

what pays the bills.

Q: Why did you start doing documentary filmmaking? What

attracts you to that?

BP: Well, I don’t even really think of documentary,

necessarily as being entirely separate from narrative or

fictional work. To me they’re part of the same spectrum.

Working with documentary you’re maybe working more

with found materials. I guess I look at it, if you want

to make analogies to visual arts, you know, sculptors and

artists who work with found materials, that’s what

a documentary is to me. Rather than creating a band or rather

than creating forty bands, I have forty bands to work with

here. Why not work with those and make the story I want

to make out of that? So, I don’t necessarily see a

difference. The only difference is that when you have great

material in front of you, you can work with that, rather

than create something entirely new.

Q: It’s interesting, what just came to my mind, is

there are different genres of working with found materials,

right? You have people who are writing biographies, people

who are writing history, current events, and things like

that. And then you have people like the Dadaists, who take

various bits of found material and put it together to make

something artistic.

BP: Well, you’ve seen the video I did for Octagrape

(a local San Diego band). The last one I did. That’s

an example of that. It’s the same thing. That material’s

out there. Those are mostly public domain films that I use,

but you recontextualize them and make them into something

new, hopefully. And that’s, I don’t know, I

mean, especially if you look at a practical level, making

a film, no matter how you do it, is an expensive and extremely

labor intensive endeavor. So if you have the material there

to work with, make your life a little easier and work with

it. [laughs] Plus all the resonances that come with it,

the historical resonances, you know what I mean? There’s

all this stuff there. There’s no reason not to use

it.

Q: So you see documentary filmmaking as kind of a combination

of telling a fact-based story, as well as creating new art?

BP: Yeah, absolutely. You know, there’s kind of a

school of thought for some people when you say you’re

doing a documentary, they think in terms of educational

films or journalism. And that’s a great element of

documentary, but that’s by no means all of it. You

can look at something like “The King of Kong,”

that documentary about the guy who plays Donkey Kong, or

even Werner Herzog’s films, they have a whole different

approach to what it is to be a documentarian. And I certainly

wouldn’t put myself in there, necessarily, at their

level, but I think I understand where they’re coming

from. That’s more my esthetic.

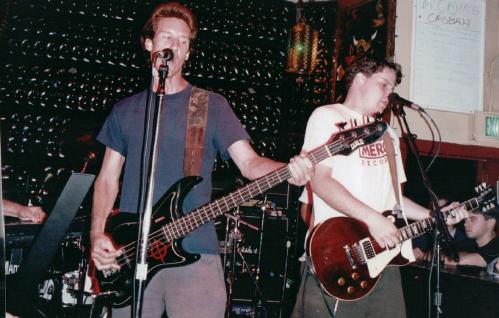

Creedle, one of the San Diego's music scene lost

treasures

Q: As you mentioned, your upcoming film release is “It’s

Gonna Blow: San Diego’s Music

Underground 1986-1996.” How did you come to choose

to do a film on this subject, and why that specific era?

BP: Well, I’m a native San Diegan. I’ve lived

here pretty much all of my life, and I lived through that

era, sort of on the sidelines. I had friends who were in

bands. I grew up with Stimy (Michael Steinman), who was

in Sub Society and Inch. And after he got signed to Atlantic,

I remember getting the demo tape back, or their first studio

recordings back, and he had them on a tape, and he was playing

them in his car, and I just remember what a crazy thing

that was, to be with your childhood friend who’s now

on this major label and going on tour and all that. And,

so, I like a lot of the bands. I think it was a high point

in San Diego’s cultural history that a lot of people,

to this day, don’t know about. In San Diego it’s

this weird little kind of cult thing. And I know people

who have lived here their whole lives and know nothing about

Drive Like Jehu or Rocket From The Crypt. But at the same

time, I dated a woman who was from Finland and her friends

came to visit, from Finland. They never had been to the

States before, and we went to see The Sultans at the Casbah,

John Reis’ little band, and there were like thirty

people there. It was like a Wednesday night, and these people

were blown away to be in the same room with John Reis. And

they were amazed they could talk to him afterwards, after

the show, and, like, shake his hand. Because, back there,

it’s a thing. There’s a cultural stamp that’s

come out of San Diego. And so, it’s great material

for a film, and it really surprises me to this day that

no one had done it already. So I was honestly waiting for

somebody else to do it, and I finally got tired of it, so

I did it. That’s literally the truth, I just got tired

of waiting.

Q: It’s interesting that you mention people from

San Diego not knowing anything about the music scene here,

and people from elsewhere being very familiar with it. I

grew up in Chicago, and, I think my introduction to the

San Diego music scene came via a Chicago band that put out

a record on Nemesis Records (a local San Diego record label

in the 1990s), a band called Billingsgate. I was friends

with them and that kind of introduced me.

BP: They were called Billingsgate?

Q: They were called Billingsgate!

BP: Alright! Great minds.

Q: Because of their release on Nemesis Records, I started

looking at other stuff on that label, and I think the first

record I bought on Nemesis Records, other than Billingsgate,

was “Saturn Outhouse” (from the band Pitchfork).

From there, I started checking out other San Diego bands,

spreading out into other labels like Vinyl Communications,

Downside Records, and all that stuff.

BP: Sure, I mean, that’s part of it, too. I mean,

this is all kind of niche music when it comes down to it,

anyway, but, I guess if you want to look at the continuum

of sort of post-hardcore music, you have these scenes, like

Louisville. People think of that as a scene, Slint and all

those bands. Chicago, you can think about Jesus Lizard and

on and on and on. DC with Fugazi and the whole Dischord

thing. I mean, San Diego really belongs up there with those

scenes, if you ask me. Maybe slightly later, if you look

at it. Definitely DC and all those guys came first. But

if you look at the quality of bands that came out of this

place, and the sheer incestuousness of it, it’s every

bit the equal of those. And yet we here in San Diego don’t

think of it that way. Even the musicians don’t think

of it that way. There are guys, fairly prominent, who really,

to this day, don’t… Even Rick Froberg (Pitchfork,

Drive Like Jehu), you hear him talk about his bands, and

it’s almost as if he doesn’t believe anybody

outside of San Diego knows about them. [laughs] Now, I think

he knows. I think he’s catching on. [laughs] It’s

a weird thing. It’s partly a San Diego thing. We’re

so self-effacing about this stuff. But, it makes these impacts

in all of these strange places. You’re all the way

over in Chicago, and there it is.

Q: When you begin a project like this, where do you begin?

How do you decide what subjects to include, who to talk

to, and so on?

BP: Well, you have to decide what makes it interesting to

you, what elements of it make it interesting to you. And,

with me, there’s definitely certain bands, a certain

style of music I’m more interested in. But there are

also certain themes I’m interested in. Like we just

talked about, I’m always interested in San Diego,

the cultural history of the place, what it means to be from

this specific place, and how that ties into this scene.

So, you have to kind of decide what interests you before

you start, and try to focus on those things. But at the

same time, you need to be open to going other directions.

And, from a practical level, I just started with Jason Soares

(Physics) [laughs], because he’s a friend, and he

really has his toes in all these different parts of the

scene. And I knew I could start with him. I’d get

a good intro to what’s going on. I could test my thesis,

so to speak. And I also knew that if I fucked everything

up he wouldn’t be furious at me [laughs] and I could

do the interview again. So, that’s really it, and

from there it goes off in all these different directions,

like corralling cats, you just have to get everything back

into place every now and then, and reassess where you’re

going, and try to keep it all on track.

Q: When you’re at the beginning of this project do

you just figure out who you want to talk to and just start

filming? Or do you plan ahead of time, maybe create a specific

story line and storyboard things out?

BP: Well, it’s kind of hard to storyboard it, per

se, but I definitely made a lot of notes to myself, and

I think I even wrote out a treatment, essentially the kind

of thing you give a producer to let him know what you’re

doing. And that helped me clarify where I was going with

it and what themes I wanted to do. So there’s kind

of conceptualizing it to a point where you’re not

just jumping in and going willy-nilly. And I did a lot of

research. But, unlike a narrative film, it’s a weird

combination of pre-planning and winging it. You have to

wing it to some degree. You don’t know what people

are going to say when you interview them, and you don’t

know where things are going to go. It is, really, a matter

of… I’m a firm believer that you really do have

to have a theme that you’re pursuing, very strongly.

And I see that with people who do documentaries sometimes

who’ve maybe never made one, and they just start filming,

and they end up with these masses of material that, because

they never really thought about what it meant, they don’t

know what to do with it. And then they’re fighting

with it for five years in the editing room to try to make

it make sense. So, it is a weird combination of knowing

what you want and being open to pursuing other avenues and

other routes. And then, on a practical level, as you go,

I had a master list of people I wanted to interview, and

it was small, like fifteen people. And then, once you get

going, all these different things come up, these little

byways, these little weird roads you can take, and you just

decide which ones you want to take that you think are conceptually

interesting, but also practically interesting. Do they live

somewhere I can go, and this kind of stuff. And so, eventually,

I interviewed over sixty people for it. Which, of course,

is not even… I could have gone for many more. But

it’s already so much packed into one film, I didn’t

do it.

Truman's Water

Q: So what is the main theme of this film, and where does

the title, “It’s Gonna Blow!!!” come from?

BP: The title comes from “Aroma of Gina Arnold,”

by Trumans Water. “Your plastic culture sucks / And

it’s gonna blow!” It’s about critic Gina

Arnold who was sort of an alterna-nation-grunge cheerleader.

Glen (Galloway) wrote the song about the commodification

of underground culture. That’s my take on it, anyway.

And, maybe, the theme of the movie is the virtues and limits

of provincialism. San Diego was and is a provincial place,

in the good and bad sense of the term. It’s somewhat

culturally isolated. And that provincialism, situated a

stone’s throw from Mexico, made us unique. So you

have a bunch of provincial San Diegans trying to “blow

up” the plastic culture and failing or succeeding,

depending on how you define success and failure. But the

title is also a reference to some people’s belief

that San Diego was going to blow up big, commercially. Thirdly,

it’s a reference to the possibility that it was going

to blow, as in suck. I’m a multi-faceted poet and

thief of lyrics.

Q: You’ve been around the San Diego music scene for

a while, and know a lot of the people from the bands of

this era. Did that make it easier to get access to the people,

archival video footage, photos, music, and so on? Or were

there still hurdles to overcome?

BP: Well that’s actually something I should stress,

because I’m really not that well connected in the

San Diego music scene. Maybe now, I am, a little bit more,

but I’m kind of a sidelines type of person, in a way.

That’s where I’m more comfortable, behind a

camera, that sort of thing. And, even though I had a few

friends from back in the day, Stimy’s passed away;

it’s been years now. The other people I knew, we’re

sort of casually friendly; we didn’t hang out very

often. And, I think that was good for me, because I definitely

had a different perspective on it than I would have if I

had been at the parties back in the 90s, do you know what

I mean? So I came to it with a fresh slate, and a lot of

people who didn’t know me, and I think I had…

everybody was very warm and welcoming, but I also think,

at some level, I had to prove myself, that I knew what I

was doing, and that it was going to be an interesting project.

And so, it’s really just a matter of making friends

who turn you onto other friends, and it’s a matter

of being, hopefully, professional enough so if you don’t

know somebody and you call them up, they feel like they’re

in good hands with you. And that’s what happened.

I didn’t really have any particular trouble getting

interviews. Sometimes it took me a few months to get everything

squared away. Not everybody’s terribly reliable at

returning calls. [laughs] But, with literally one exception,

everybody has been incredibly cool through the whole process.

They’ve been very welcoming and very warm, and it’s

been a wonderful experience. I’ve made a lot of friends

through it, but I came in as a bit of an outsider, and I

think that helped me.

Drive Like Jehu

Q: How easy or difficult was it to get the archival footage,

photos, and music to include?

BP: That just takes a lot of persistence, frankly. That’s

just bugging people all the time. And I had the Facebook

page, which was a big help for that. Some of my best material

came out of nowhere. People just happened to have something

in a closet. I got things that have… you know, they’ve

been sitting in closets for 20 years. I have some really

great stuff. I think it literally would have rotted away

if I hadn’t done this film. I don’t think it

would have ever come out. That being said, I’m still

waiting on material from some other people [laughs] who’ve

told me they have these great archives, and they’re

good people, maybe they’re just a little bit flaky.

I’ve just never gotten it out of them. And, at this

point, it is that; I do have an archive. Beyond the film,

itself, I’m going to do something with it. I don’t

know what.

Q: Some of the bands and some of the people have, shall

we say, interesting quirks. Tell us about some of the more

interesting characters you’ve included in the film

and some good stories you can tell us from the interview

sessions.

BP: Oh, gosh, where do I start? Tim Blankenship was a fun

one. Tim’s from Creedle and Rust, and a couple other

bands. Basically, we all got drunk and did that interview.

Actually, that’s not true. I should be honest. Tim

got drunk. [laughs] I was sober through the whole thing.

We met up at the Waterfront Bar, and Tim had already had

a couple by the time we got there. We wandered through all

these old haunts. We went to Wabash Hall, over on University,

which is an old punk venue. We went to the “old”

and the “new” Casbah. We went to all these different

places and filmed on the streets, and ended up at another

bar and filmed an interview there. That was wild, just because

Tim was very outspoken after awhile [laughs] to the point

where I cut some of his stuff out of the film, because I

was worried maybe he was being a little too honest about

things. So that was great. Dealing with the Crash Worship

people was really interesting.

Q: How so?

BP: Well, one of them who I wanted to interview, I never

got to interview. And, I’m convinced it was all an

elaborate Crash Worship style mind-fuck on me [laughs] to

this day. Other people tell me that’s just his personality.

But it got to the point where I thought I was maybe going

insane, because I couldn’t tell quite what he was

trying to do to me. I interviewed Markus (Wolff), who ended

up being very nice, up in Portland, and completely not what

you would expect of somebody from Crash Worship. He was

very mild mannered and very quiet. Ian MacKaye and Brendan

Canty from Fugazi, I interviewed them. That was amazing.

Q: How does that tie into the San Diego Music scene?

BP: Big Pitchfork fans. They played with Pitchfork, and

they… I don’t want to spoil it, but mention

in the film… well, there’s really nothing to

spoil. They regarded Pitchfork as every bit the equal to

Fugazi. They were just contemporaries, and they admired

them a lot. And, also, Ian had some funny experiences here

in the 80s at the punk shows, when things were still kind

of violent and crazy. But that was a hoot, just hanging

out at Dischord Records all day long, while Ian played DJ

and played me his favorite bands. It was an experience to

remember. But every single interview was interesting in

some way. All of them are half crazy and wonderful people,

so every single one was really a lot of fun. Oh, the Trumans

Water guys (Kirk and Kevin Branstetter)! That’s a

good one to mention. Because we went up there, and Kirk’s

dog had had seizures the night before, and it had amnesia.

And, so, through the entire interview it wouldn’t

leave Kirk and Kevin’s side. And it was constantly

making noise and farting. [laughs] We had to shut down production

because of the stench that was wafting through the room.

You combine that with Kirk and Kevin being like a comedy

team, it was just a lot of fun. That was a great shoot.

Q: Did you uncover any surprises during the process of

making this film?

BP: Well, I certainly didn’t uncover any great secrets,

in terms of… there’s not a ton of, like, early

New York punk scene drama. People didn’t stab each

other, nothing like that. I think the surprise is, maybe,

what we were talking about earlier, and that’s people’s

conception of the music scene, and their place in the musical

firmament. There’s this sort of relentless…

even somebody like John Reis, who has, especially when he’s

Speedo, he has this kind of over-the-top, almost pompousness

about him. You know, he’s a god of rock and roll.

And you talk to him when he’s out of character, and

he’s self-effacing, almost to a fault. There were

times in our interview where it was hard to get him just

to talk in a straightforward manner about Rocket From The

Crypt and (Drive Like) Jehu. I still think he conceives

of them, and this is a good thing, as a local phenomenon,

a local band that happened to tour a lot. I don’t

think he considers the impact they’ve had on a lot

of people. And that’s very surprising to me, to this

day. You were at the Jehu concert, you saw. People flew

in for that fucking thing. It’s insane. And people

were crying. There were people crying at that first song.

So that may be the biggest surprise. There were lots of

little surprises, I think people who are real nerds about

this stuff will pick up on. But the biggest surprise is

just how, it started out as a DIY thing and it got big.

But, at heart, it’s still very DIY, and that’s

how these people think of it. They never really changed

their perspective on it. At least the people in the core

of the scene.

Q: Were there some people you wanted to interview but couldn’t,

either because they weren’t available or didn’t

want to be involved?

BP: There were a few. The big one was Rick Froberg. And

that was probably more of a logistical thing, because he’s

in New York, and he was traveling in Spain and all that.

But also, Rick’s maybe not the most talkative person,

as far as interviews go. I’m friendly with him, he

did the art for the film, and he’s seen the film.

He liked it, which meant a lot to me. But he really doesn’t

like doing interviews. We made some attempts at that. It

never happened. Maybe it will for the (DVD) extras. And

then, O (Olivelawn, Fluf). O’s such a great part of

the scene, but he’s another guy who doesn’t

like being on camera, simple as that. Again, I’m good

friends with him and he’s been very supportive, but

he just didn’t want to get in front of that camera.

Otherwise, I got pretty much everyone I wanted, with the

exception of Eddie Vedder (Pearl Jam), but I didn’t

think that was going to happen, anyway. [laughs]

Q: How long did it take, from concept to finished product,

to make this film?

BP: It was a little over two years, which is quick. Frankly,

that’s a testament to, well, it’s a testament

to how much work I put into it. I put a lot of things aside

to really concentrate on it. And it’s also a testament

to how wonderful people were. Once they got word of the

project, once the first trailer came out, people helped

me a lot, in terms of getting me material and being available

for interviews, and things like that. And my crew. I should

mention, I had people helping me on that end who really

stepped things up for me. But something like this can take…

I think “American Hardcore,” that documentary,

took something like ten years to make. And I did not want

to do that. [laughs] When it came down to it, I’m

very happy with the timetable. It was just about right.

Q: Was it primarily a solo effort, of have you gotten help

along the way?

BP: I had a soundman who came with me on 90% of the shoots,

and he also acted as kind of everything else, Rick Bowman,

who’s a filmmaker in his own right. Rick’s not

even a fan of this music. He doesn’t dislike it, but

he’s a fairly traditional music type guy, classic

rock and that sort of thing. But he was so taken in by the

people and how fascinating they were that he did so much

work for me, so many shoots. We probably did fifty shoots

together. That’s a lot. And I had the occasional cameraman

come to help me out when they could. But, in the end, I

think I shot 80% of the film myself. And these were two-camera

shoots. It was a fairly elaborate thing, as these things

go. But, I edited the film myself, I produced it. I guess

it’s kind of like being in a band. I was the main

dude, but I had a lot of people helping me to get it out.

Q: You talked about the supportiveness of people for the

project. Did that extend to helping with funding?

BP: You know, we did a Casbah benefit concert, which raised

a little bit of money, which was fantastic. If anything,

I haven’t made a lot of effort to get funding from

people. Which is my own neurosis, I suppose. I like the

feeling of complete freedom, knowing that it’s my

ass on the line. So, no, I didn’t really ask for any

funding. And, other than the Casbah concert, I really didn’t

get much. But I did have people more than hint that they

were willing to give me some money, and I didn’t take

them up on it. After the film comes out and I need to pursue

touring and distribution, things like that, if people like

the film, I think I’ll look for more money at that

point. I feel better about it, that way. I didn’t

want to take advantage of the general DIY supportiveness

of this scene to ask for money for a project that they may

or may not like. I think they’ll like it, but who

knows? Once they see it they can decide if they want to

give me money to help it actually get seen more.

Q: You mentioned this little fundraiser at the Casbah,

but it was actually pretty epic. So tell us about that.

What happened there?

BP: That was San Diego’s Finest. That was amazing.

One of the nicest things about doing this documentary is

I’ve become very good friends with Rob Crow (Physics,

Heavy Vegetable, Thingy, Pinback). We’re a lot alike

in certain ways. He’s just much more talented than

me! [laughs] But Rob’s been really wonderful through

the whole thing, incredibly supportive. And when he heard

we wanted to do this benefit, I asked him, and I just assumed

he maybe would do a short solo set, something relatively

simple. But he immediately volunteered to put together,

essentially, an all-star band that would play the history

of San Diego music from this period. And that’s what

he did. It was crazy! He basically had a… I use this

analogy because I know Rob would hate it with the core of

his being. It’s like the Ringo Starr All-Starr Band.

[laughs] Suck on that, Rob! [laughs] But, basically, it’s

Rob as the leader of the band, and he had sort of a dedicated

backing band, and he brought in all these luminaries from

San Diego’s history to play everything from three-chord

straightedge punk to weird-ass Trumans Water and No Knife

songs. It was great, it was amazing. And it was a wonderful

night, just to see people come out and it was kind of a

big reunion in a lot of ways. So that was wonderful, yeah.

Q: Were there times when you wondered if all the effort

was worth it, and contemplated dropping the project?

BP: Well, I did briefly drop the project, actually. That

was at the beginning. But that was more for technical reasons.

Our first few shoots, I didn’t like the way the footage

looked. And so I stopped it for a few months. I was doing

research and stuff like that on it still, but I just stopped

working on it at the very beginning. I never actually considered

dropping it, but there are constantly times when I wonder

if it’s all worth it, because it really is an insane

amount of work. And, as supportive as people are, they don’t

understand how much does go into it. Especially, I think

people are going to be surprised at how the film looks,

because there’s a certain level of expectation with

punk rock documentaries, and, to my mind, it’s occasionally

a bit low. [laughs] The bar is set a little bit low. And

even some of the ones I really love, they really put no

effort into making it look like a good film. And that’s

OK, but I really did make a lot of effort, on my budget,

to make it look nice. So, yeah, there are times when you’ve

emailed somebody for the thirtieth time and they haven’t

responded, or somebody offers to do an interview and they

want to do it in the middle of traffic somewhere [laughs]

where the sound is going to be terrible, where I do get

frustrated and I do kind of wonder if it’s all worth

it. But then, all it really takes is just, whatever, having

Pall Jenkins (Three Mile Pilot) or somebody say how stoked

they are you’re doing it. Or having Rob say something

nice, or having some stranger write to me from Poland saying

they want to see it, and it all seems worth it again.

Q: You’re having the first screening, I don’t

know if you’re calling it a premiere or a preview,

on October 9th, at the Victory Theater in San Diego. Tell

us what we can expect to happen there.

BP: Well, technically, I’m calling it the Director’s

Cut, even though I hate that term. But that’s what

I’ve decided to call it, because there’s some

material in there that may have to be cut before it goes

out for wider distribution. So this may be one of the few

chances to see the film the way I’d like to show it.

And it’s just going to be a big party. We’ll

keep it real loose. Rob Crow is going to do a little DJ

set, we’re going to show the film, and we’re

going to go over to The Hideout (a club in San Diego’s

City Heights neighborhood) and have some bands and some

beer and have a good time. I want it to be special, but

also very low key and very San Diego. No red carpet or any

of that kind of bullshit. If we want to do that down the

road we can do it. [laughs] There had been some talk about

doing a “friends-only” screening at the Casbah

where people who were in the film could come and see it,

and I decided I wasn’t quite as hot on that because

I wanted it to be a chance for everybody to mix together.

What I like about this screening is that, hopefully, you’ll

have John Reis and some kid from Poway (San Diego suburb),

who’s never even seen any of these bands live, sitting

next to each other. And that’s what I wanted. I wanted

it to be something for everybody. After that we’ll

get into maybe more specific screenings. But I wanted this

to be a chance for everybody to come together, hopefully,

to experience it together.

Pitchfork: Before there was a website, there was

a band

Q: What’s your plan for the film beyond this preview?

Will you take this onto the festival circuit? Will you do

a DVD? How will you distribute it?

BP: Well, it will come out on DVD and digital and all that,

probably either late this year or early next year. I have

some stuff I have to take care of before I can do that.

In the mean time we’re going to have, I’m putting

it together right now, so I’m a little cagey about

it, but we’ll probably have a couple little tours

of it. Maybe an east coast and a west coast run. And then,

hopefully, some festival screenings, one-off screenings,

things like that. It’ll get around, I’d like

to show it as much as possible in theaters and alternative

venues, hopefully with me present, because that’s

half the fun, really. You work on something like this and,

it’s like being in a band, I guess. You work on your

album and the fun is going out and being able to play the

music for people, meet people, and experience their reactions.

If I were just to put it out on DVD, that would be no fun

at all. So people have lots of chances to see it, one way

or another.

Q: Is there anything you would like to add?

BP: Probably not. But thank-you for your interest, and thanks

for being supportive all this time. I really appreciate

it.

For more information, on this film, check out the website,

www.billingsgate.org/sdmusicdoc.

JerseyBeat.com

is an independently published music fanzine

covering punk, alternative, ska, techno and garage

music, focusing on New Jersey and the Tri-State

area. For the past 25 years, the Jersey Beat music

fanzine has been the authority on the latest upcoming

bands and a resource for all those interested in

rock and roll.

|

|

|