Film Review:

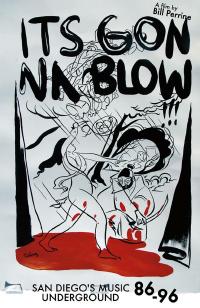

It’s Gonna Blow!

San Diego’s Music Underground 1986-1996

By Paul Silver

The

title has a double meaning. The first refers to the music

critics and major labels who were saying, in the early 90s,

that the San Diego music scene was going to blow up big

time and be the next Seattle. The other meaning, as embodied

in the lyrics from the Trumans Water’s song“Aroma

of Gina Arnold,” refers to the “plastic culture”

presented by these musical leeches, and that what they offered

was going to blow, as in suck. Both of these meanings are

explored in the new documentary from filmmaker Bill Perrine,

“It’s Gonna Blow! San Diego’s Music Underground

1986-1996.” The

title has a double meaning. The first refers to the music

critics and major labels who were saying, in the early 90s,

that the San Diego music scene was going to blow up big

time and be the next Seattle. The other meaning, as embodied

in the lyrics from the Trumans Water’s song“Aroma

of Gina Arnold,” refers to the “plastic culture”

presented by these musical leeches, and that what they offered

was going to blow, as in suck. Both of these meanings are

explored in the new documentary from filmmaker Bill Perrine,

“It’s Gonna Blow! San Diego’s Music Underground

1986-1996.”

The film attempts to tell a very specific story. It’s

not a comprehensive retrospective of the birth and growth

of the San Diego scene. In this way, it differs significantly

from many other documentaries that attempt to trace the

history of a city’s particular punk or underground

music scene. Rather, it tells the story about a scene that

had to reinvent itself a couple of times, a scene that was

deeply rooted in the DIY ethic, and a scene that struggled

with the sudden, unexpected attention from an outside world,

while they still labored in relative obscurity at home.

And it succeeds in telling that story.

Like other documentary films covering various music scenes

around the country, “It’s Gonna Blow!”

uses a mix of interviews with former band members, archival

video, photos, flyers, and recordings of music from the

day. But the way in which it presents these things has some

interesting differences. The introduction has a clever,

humorous bunch of edits, first introducing us to the San

Diego that most people think of, but then bringing us this

“other” San Diego, the one that was the underground

scene. George Anthony’s (Battalion of Saints) rapid-fire

cuts are particularly funny, but there’s also a bit

of a sense of melancholy from the interviewees, like Tim

Blankenship (Creedle, Rust), as he recalls that the prediction

that San Diego would be the next Seattle never quite worked

out.

Another very effective difference in this film is in the

settings for the interviews. Most documentaries of this

sort just have the people sitting in a chair in a living

room or something like that. Here, the locations and surroundings

give a unique look to the film. Anthony is seen in a cemetery.

John Reis (Rocket From The Crypt, Drive Like Jehu, Pitchfork)

is outside of a men’s room. Mike Down (Amenity) is

at a dirty table outside the Che Café on the UCSD

campus. Justin Pearson (The Locust) is on a leather sofa

beneath a large animal skull mounted high above on the wall.

One of the most poignant locations was that of Lou Niles

(former San Diego radio DJ at 91X and manager of the band

Inch), who was sitting in a booth at The Live Wire, one

of San Diego’s premiere dive bars. Hanging on the

wall over the booth is a guitar and other memorabilia that

belonged to Stimy (Michael Steinman), of Sub Society and

Inch, who sadly passed away a few years ago.

The film tells its story, pretty much in chronological

order. The backdrop of the early, violent hardcore scene

is set, with stories and video footage of gangs, bikers,

and skinheads starting fights at shows and stealing equipment

from bands, even as they were on stage playing. The reaction

of the actual bands and fans who wanted to see them was

to withdraw and then restart the scene, sort of in hiding

from these bad elements. Tim Mays stopped doing shows for

a bit, opening the Pink Panther bar, and eventually The

Casbah, which became one of San Diego’s most important

venues. The Che Café was hosting the new breed of

bands, with eclectic shows featuring a differing variety

of bands. And out of these places and people, the San Diego

music community was born.

The film features an interesting cast of characters reminiscing

about the era. Of course, local musicians who were there

are heavily featured, but also included are outsiders giving

another perspective. Milo Aukerman (The Descendents) makes

an appearance, as do Ian MacKaye and Brendan Canty (Fugazi).

The story moves into the building of this new community,

centered around places like the Casbah and record labels

such as Bob Barley’s (Neighborhood Watch, Tit Wrench)

Vinyl Communications and, of course, Cargo Records. And

it focuses on the sea change brought about by outside influences

from Washington, DC and Louisville, Kentucky, in the form

of the band Pitchfork. This was, as Mitch Wilson (Funeral

March, No Knife) notes, a game changer, and people saw,

as he says, “what was possible.”

What was possible, as Chris Prescott (Fishwife, Tanner)

says, was that the bands could do whatever they wanted,

because they were just doing it with their friends. And

do whatever they wanted, they did. The diversity of music

exploded, as did the on-stage antics.

The scene continued to evolve, as the film shows, and Pitchfork

and Night Soil Man gave way to Drive Like Jehu, pulling

in influences from bands like Bastro and Slint. And Rocket

From The Crypt, as John Reis says, was his way of trying

to bring an earlier punk rock influence back into his music,

after the violence from that early scene was gone. The film

then starts to focus pretty heavily on these two bands and

the bands they influenced, the rise of Cargo Records, San

Diego’s largest indie label, and the attention that

was drawn to them from the majors.

The early 90s was a time when the major labels were trying

to snap up any bands that had the new “alternative”

sound, and several San Diego bands, though thoroughly DIY

in nature, were something these labels wanted (or thought

they wanted). Trumans Water attracted the attention of John

Peel, who flew the band over to England to appear on his

BBC radio program and play the Reading festival. And Interscope

grabbed Jehu and Rocket. Rocket’s contract was amazingly

unique in that it allowed them to continue putting out 7”

singles with other record labels, and Jehu had creative

freedom over their records, including artwork.

The scene developed sort of a split personality, with these

bigger, more well known bands reaching larger audiences,

yet the other bands were continuing to “do whatever

they wanted,” bringing an ever increasing creative

diversity to the scene. But what was eagerly accepted outside

San Diego, with large audiences (Trumans playing to 5000

people in England, Crash Worship playing to 500-1500 at

a time) was oddly under appreciated back at home. These

cutting edge bands would barely attract a handful of other

people at shows at home. And, yet, the majors started snapping

up more and more bands from San Diego.

The film explores the interesting cynicism of the San Diego

bands toward these interloping majors, with some creating

bands just to get signed and play music for the masses to

make money, while still doing their “real” bands

for people who understand and appreciate “real”

music. And it even went as far as some people creating a

hoax band that didn’t exist, putting out fake press

items for a band that never had played a single show, just

to see what sort of reaction they would get from the A&R

people. And they did get people sniffing around asking about

this “Thorpe” band. Things were spiraling out

of control, says Cargo Records’ Bryan Spevak.

Eventually, the majors realized that they really didn’t

know what to do with a lot of these bands they had signed.

So, as they had done before in other cities, they picked

up and moved on. And the few bands that had gotten a bit

of “traction” with the majors decided they didn’t

really want to play the game by their rules to keep things

going.

And so the San Diego scene reinvented itself yet again.

But, through all these changes and reinventions, things

were sort of always the same, in a way. It was bands doing

their own thing, doing it with and for their friends, and

no one else, really. And, doing it without realizing how

much they have influenced other people around the country

and around the world.

It’s tempting to complain about the omissions from

this film. Bands that were a significant part of the San

Diego scene, like Olivelawn and Fluf, are not included,

and key people like Rick Froberg and O aren’t interviewed.

And, as the film explores how the same group of people continues,

to this day, to make music for themselves and each other,

it would have been nice to talk about the younger bands

that San Diego has spawned out of the old. But, like I said,

this isn’t meant to be a comprehensive historical

document. It tells a particular story. I didn’t get

that going into my first viewing at the film’s premiere

in October. But with a couple more viewings under my belt,

I understand that story and the message behind it, and it’s

very effectively conveyed. So I no longer consider those

to be omissions.

“It’s Gonna Blow is making its way around the

country this winter for special screenings, so check out

www.facebook.com/sdmusicdoc and click on the Tour Dates

icon for information on a screening near you. A DVD and

digital download release is planned for sometime in 2015,

and Perrine promises some interesting extras, so keep an

eye out for that, too. I recommend you catch the film’s

screenings, though, as there are special surprise guests

planned at some of them, and Perrine will be on-hand for

Q&A, as well.

JerseyBeat.com

is an independently published music fanzine

covering punk, alternative, ska, techno and garage

music, focusing on New Jersey and the Tri-State

area. For the past 25 years, the Jersey Beat music

fanzine has been the authority on the latest upcoming

bands and a resource for all those interested in

rock and roll.

|

|

|