|

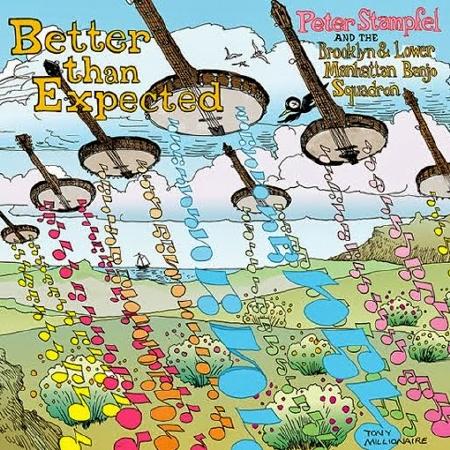

In Part One of our interview, we talk about Peter's latest

album, Better Than Expected, by Peter Stampfel

& the Lower Manhattan And Brooklyn Banjo Squadron. That

segues into a history of the banjo in American popular music.

Q: Let’s talk about the new album first. My understanding

is that this was an experiment to see how many banjos you

could have playing at a time without it turning into total

anarchy.

Peter: Well, then again, anarchy works. (laughs) The question

is, how far can you go? Having a limited number of musicians

in a band makes everything much easier. Once you get beyond

four, it starts getting tricky. Up to four, it’s fairly

easy for everyone to hear everyone else. Once you get five,

five is a lot harder than four. And as you add numbers,

the difficulty becomes exponentially greater. Six is a lot,

lot harder than five, and seven is a lot, lot harder than

that.

In the real world, I keep running into people I play with

and want to include in whatever project’s going down.

This is the dao of the world. This is what I’m constantly

confronted with. Oh, I gotta play with this guy, gotta play

with this guy too. So at a certain point, you go, okay,

one more and that’s it, and then finally I just said,

fuck it, I’m not going to restrict the upper number.

Like I write in the liner notes, half the potential members

of the banjo squadron weren’t available when the tiny

window for recording revealed itself. So we’ve never

had more than five banjo players going at once, despite

the fact that there were ten or more potential people I

wanted. And my idea was, after a certain point, say after

five, I was going to split the banjos into two groups, A

and B. This album is an experiment on several levels. I’m

not doing it so certain things will happen; I’m doing

it to find out what happens if we do it. When you approach

an artistic project with the idea, “I don’t

know, I have no fucking idea what’s going to happen,”

it just opens up everything wonderfully. Instead of having

some sort of formulaic, didactic plan. So I was going to

split the banjos into two bunches, and have the first group

play on four beats or eight beats, or two beats and one

beat, and have the second group play on two, four, eights,

sixteenths. And have group A play four beats, group B play

four beats, and then everybody play four beats. The idea

being, once you get that many people, it constructs things

so that despite the crowd, the potential number of people

playing at any one time forces some people not to play but

to listen. Because listening is the whole point of being

in a band. That’s why three or four people is the

ideal band, especially when you’re improvising, because

they can all listen to each other. Listening is just incredibly

critical when you’re free-forming. Otherwise you get

mud. So the idea here was to have some kind of magic happening

with multiple people where half the group was being forced

to listen to the other half at least part of the time.

Q: The banjo is an interesting instrument, though,

because if you have two guitars, you can play harmonies,

like the Allman Brothers. Banjos don’t really do that.

Peter: Oh they can, they can indeed. In fact harmonies

are my favorite way of improvising. If you’re harmonizing

with somebody, you’re automatically in rhythm. You

can’t possibly harmonize with someone and not be following

the same beats. I love fifths, I love fourths, I love weird-assed

harmonies like a fifth above and a fourth below. I like

harmonies that ideally make the hair on the back of your

neck stand up.

Q: It seemed to me like the banjo fell out of favor

for a long time and recently they’ve been revived

by all these alt-Americana bands like Mumford & Sons

made them chic again. But I know most folk purists don’t

like that band. How do you feel about it?

Peter: Banjos were the rock and roll of the 19th Century.

Banjos were absolutely massive. There’s the cliché

of the cowboy with a guitar, but guitars in the 19th Century

were an upper middle class woman’s parlor instrument.

Guitars didn’t become popular until the Spanish-American

War. The lower class and lower middle class soldiers picked

up guitars in Cuba and brought them back to the U.S., and

a substantial number of black musicians at that time laid

their banjos and fiddles down and picked up a guitar. I

mean, guitars are fucking amazing things, you can see why

they became so popular, especially with blues musicians.

Then the four-string banjos came into popularity because

of ragtime music and early jazz, and you had to compete

with a bunch of horns, so you needed resonators and flat

picks. Then banjos began fading again in the 1930’s

when electric guitars came into vogue. They never amplified

banjos, oddly, but guitars and amplification were a marriage

made in heaven. By the 1930’s, your professional banjo

players had to wear clown drag. Even Uncle Dave Macon had

a real clown shtick going. And you had country people like

Grandpa Jones and Stringbean who wore bib overalls and low-cut

pants and all had a comedy thing going, because banjos just

weren’t taken seriously at that point.

Q: Except for bluegrass.

Peter: Well, that’s an interesting story. I had a

friend in Milwaukee who introduced me to folk music in 1957.

This guy named Ron Tiafan who was from Texas, he was going

to Marquette University studying dentistry, but he played

5-string banjo. He played on Louisiana Hayride, which was

a big country radio show, and he played in a talent show

at Marquette. He had a top hot with the top ripped off and

ripped jeans, it was a strange meme of banjo playing being

equated with being a yokel clown.

Bluegrass music actually came into being based roughly

on what Charlie Poole was doing with his finger-picking,

and he played like that because Charlie Poole played baseball,

and he was too macho to use a glove. So he caught a fly

ball with his bare hand once and broke his fucking hand,

and it set into a position where he could do three-finger

picking but that’s about all he could do. He couldn’t

bend his hand to hold a pick or hit any more strings. And

then Flatt & Scruggs came along with that same finger-picking

style, about 1939 or so, and that became bluegrass.

Pete Seeger is about one-half responsible for the banjo’s

popularity among non-Southerners. Back in the Fifties when

Pete Seeger became more widely known, he introduced the

banjo to a whole new audience of urban listeners and it

never really died out since then. And I’d say there’s

been a steady growth with an occasional growth spurt. But

I’d say that the popularity of banjos, if you were

going to draw a chart, number of banjos sold and people

playing them, I think your chart would be going steadily

upwards from the Fifties. And people are still picking up

on it. What’s that pop record? “Best Day Of

My Life.” That has a really cool banjo sound in there.

It’s got a nice banjo part. A perfect example of how

excellently finger-picked banjo can be incorporated into

contemporary rock ‘n’ roll. I see on Youtube

all the time more and more people playing banjo along with

the standard rock and roll instruments, which I’m

very happy about.

Continue

to Peter Stampfel, Part Two Continue

to Peter Stampfel, Part Two

back to jerseybeat.com

l back to top

JerseyBeat.com

is an independently published music fanzine

covering punk, alternative, ska, techno and garage

music, focusing on New Jersey and the Tri-State

area. For the past 25 years, the Jersey Beat music

fanzine has been the authority on the latest upcoming

bands and a resource for all those interested in

rock and roll.

|

|

|