| |

Interview by James Damion

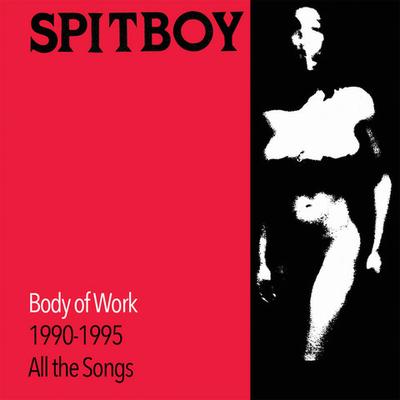

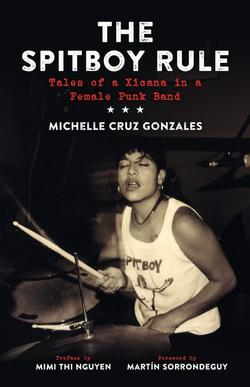

Michelle Cruz Gonzalez is an author, English instructor, activist, public speaker, Mom, and the former drummer/co-founder of the groundbreaking East Bay hardcore punk band Spitboy. After returning to the East Coast with a long list of records I wanted to add to my cache, I took a trip to Baltimore’s Celebrated Summer Records where, amongst other purchases, I took home Spitboy's Body of Work (1990 – 1995). While having all of the band's recorded work in one place was appealing, I had no idea how deeply those songs would impact me. In reaching out to Michelle, I was looking to take a deeper dive into Spitboy, her experiences as a drummer, and perhaps the reasons why the band was so adamant about not being associated with the term "Riot Grrl."" Thankfully, she gave me so much more. In addition, Michelle introduced me to terms such as "Xicana," "Meno Punk,"" and the alternative spelling of Women, "Womyn."

Q: What were your introductions to punk and hardcore? Can you describe some of your early experiences and interactions?

Michelle: The first punk band that I heard ,or registering with me, was definitely the Clash. Before the Clash I was really into The Go-Go’s, but I didn’t really realize then that they had been a punk band too. I actually saw the Clash in 1983 at the US festival. It was their last year with Mick Jones and Because the show is in Southern California, Joe Strummer called out Mexican-Americans and said that society wasn’t just going to be one white way down the middle of the road. It sort of bowled me over, made me really happy to be see.

Q: How long were you going to shows before you realized you really wanted to be in a band?

Michelle: Directly after seeing the Clash, we started going to San Francisco to see bands like the Dead Kennedys at Mabuhay Gardens. My best friend Nicole Lopez, who was also in Bitch Fight, her mom drove us to see punk shows because she liked punk and all the politics. We went to the 1984 Democratic national convention protest site rock against Reagan show and saw a dead Kennedys the Dicks, Reagan US, and a bunch of other bands. The rock against Reagan T-shirt that I bought that day, a pink tank top, is now in the Smithsonian exhibit on girlhood.

Q: It’s funny you mention The Clash. “London Calling” was the first record I ever bought with my own money. It blew me away and made every other album I’d own and had owned lack in comparison. Shortly after, I somehow convinced my Mom to take me to see them at a place called Bonds Casino.

Michelle: I love your Mom for taking you to see The Clash.

Q: Correct me if I’m wrong. But you were in a couple of bands before Spitboy. Can you share your experiences?

Michelle: Yes, my very first band was called Bitch Fight. We formed in TUOLUMNE, California, a very small town in the gold rush country. I started that band with Nicole Lopez and Sue Carney. We were all daughters of single women on welfare. After living in San Francisco for about a year and a half together, Bitch Fight broke up, and then I joined Kamala and the Karnivores for a bit. I happened to be in the band when they recorded their Lookout 7 inch. You could maybe say that I’m like a Forrest Gump of punk rockers -- I went to some iconic shows, played in some iconic venues, and in and with some iconic bands like Fright Wig, Operation Ivy, Tiger Trap, and Green Day.

Q: Can you give me a little background on you bandmates and what is was that made the members of Spitboy click?

Michelle: I mean, we were a bunch of women who wanted to be in a band with women not men. I specifically never wanted to be in a band with men. Paula and I became friends in the scene because we were both working with small children at the time. Paula knew Karin from blacklist mail order volunteering, and I met Adrienne through my then boyfriend Neil who wound up being in the band Paxton Quiggly. The Spitwomen clicked because we were all feminist in the scene facing a lot of the same issues, and we wanted to play loud hard fast angry music without being seen as a novelty act.

Q: At the time, and even now, punk, hardcore and, in particular, Anarcho Punk were a male dominated scene that was often exclusionary to women. Can you share some of the reaction you got from show goers and people in the scene?

Michelle: In the bay area, the response to Spitboy was pretty positive, but I always got the sense that the men in the most popular bands didn’t really know how to react to us. They were like, cool, cool, but it’s not like they would come to see us play unless we were actually playing with their band. If we were playing with her bands, they were usually headlining. Interview by James Damion

Michelle Cruz Gonzalez is an author, English instructor, activist, public speaker, Mom, and the former drummer/co-founder of the groundbreaking East Bay hardcore punk band Spitboy. After returning to the East Coast with a long list of records I wanted to add to my cache, I took a trip to Baltimore’s Celebrated Summer Records where, amongst other purchases, I took home Spitboy's Body of Work (1990 – 1995). While having all of the band's recorded work in one place was appealing, I had no idea how deeply those songs would impact me. In reaching out to Michelle, I was looking to take a deeper dive into Spitboy, her experiences as a drummer, and perhaps the reasons why the band was so adamant about not being associated with the term "Riot Grrl."" Thankfully, she gave me so much more. In addition, Michelle introduced me to terms such as "Xicana," "Meno Punk,"" and the alternative spelling of Women, "Womyn."

Q: What were your introductions to punk and hardcore? Can you describe some of your early experiences and interactions?

Michelle: The first punk band that I heard ,or registering with me, was definitely the Clash. Before the Clash I was really into The Go-Go’s, but I didn’t really realize then that they had been a punk band too. I actually saw the Clash in 1983 at the US festival. It was their last year with Mick Jones and Because the show is in Southern California, Joe Strummer called out Mexican-Americans and said that society wasn’t just going to be one white way down the middle of the road. It sort of bowled me over, made me really happy to be see.

Q: How long were you going to shows before you realized you really wanted to be in a band?

Michelle: Directly after seeing the Clash, we started going to San Francisco to see bands like the Dead Kennedys at Mabuhay Gardens. My best friend Nicole Lopez, who was also in Bitch Fight, her mom drove us to see punk shows because she liked punk and all the politics. We went to the 1984 Democratic national convention protest site rock against Reagan show and saw a dead Kennedys the Dicks, Reagan US, and a bunch of other bands. The rock against Reagan T-shirt that I bought that day, a pink tank top, is now in the Smithsonian exhibit on girlhood.

Q: It’s funny you mention The Clash. “London Calling” was the first record I ever bought with my own money. It blew me away and made every other album I’d own and had owned lack in comparison. Shortly after, I somehow convinced my Mom to take me to see them at a place called Bonds Casino.

Michelle: I love your Mom for taking you to see The Clash.

Q: Correct me if I’m wrong. But you were in a couple of bands before Spitboy. Can you share your experiences?

Michelle: Yes, my very first band was called Bitch Fight. We formed in TUOLUMNE, California, a very small town in the gold rush country. I started that band with Nicole Lopez and Sue Carney. We were all daughters of single women on welfare. After living in San Francisco for about a year and a half together, Bitch Fight broke up, and then I joined Kamala and the Karnivores for a bit. I happened to be in the band when they recorded their Lookout 7 inch. You could maybe say that I’m like a Forrest Gump of punk rockers -- I went to some iconic shows, played in some iconic venues, and in and with some iconic bands like Fright Wig, Operation Ivy, Tiger Trap, and Green Day.

Q: Can you give me a little background on you bandmates and what is was that made the members of Spitboy click?

Michelle: I mean, we were a bunch of women who wanted to be in a band with women not men. I specifically never wanted to be in a band with men. Paula and I became friends in the scene because we were both working with small children at the time. Paula knew Karin from blacklist mail order volunteering, and I met Adrienne through my then boyfriend Neil who wound up being in the band Paxton Quiggly. The Spitwomen clicked because we were all feminist in the scene facing a lot of the same issues, and we wanted to play loud hard fast angry music without being seen as a novelty act.

Q: At the time, and even now, punk, hardcore and, in particular, Anarcho Punk were a male dominated scene that was often exclusionary to women. Can you share some of the reaction you got from show goers and people in the scene?

Michelle: In the bay area, the response to Spitboy was pretty positive, but I always got the sense that the men in the most popular bands didn’t really know how to react to us. They were like, cool, cool, but it’s not like they would come to see us play unless we were actually playing with their band. If we were playing with her bands, they were usually headlining.

Q: While living in Seattle I became friends with a record store manager who was originally from the bay area. Each time we spoke we’d relay stories from his West Coast upbringing while I would mention my life in New York City. The way he talked about The East Bay scene and volunteering at the Gilman project more than convinced me just how special that time and scene were. Can you share any memories or anecdotes regarding your experience there and how you became involved with the documentary “Turn it Around,”?

Michelle: I was asked to be interviewed for the doc early on, and I was interviewed in like 2014. I had already started writing the essays that are in my memoir The Spitboy Rule. While I don't see them super often, I have remained friends with Billie Joe from Green Day and Jason White their touring guitarist. Green Day and the director wanted to make a movie that represented the scene as best they could. They didn't want to make another movie about white punk rock dudes. They interviewed people in bands, reached out to the POC in bands, they interviewed several women who weren't in bands, but were around all the time, volunteering at Gilman, people who ran record labels, and generally supported the scene in other ways besides being bands. I was in three bands that played at Gilman: Bitch Fight, Kamala and the Karnivores, and Spitboy, so they had to interview me. I grew up there and hung out with the guys in Crimpshrine, Operation Ivy, Green Day, and a bunch of the young women who went to all the shows. There was a crew up of us Stacey White, Marcia, Rebecca Wong, Kerith Pickett, and others would stand by the stage outside of the moshing area and just dance, like really dance. I was in bands, but I was a fan too. I went to Gilman nearly every weekend from the time I was 18 - 27. I dated a lot of guys who played in bands at Gilman too, but I didn't want to talk about that when I was being interviewed because who wants to be known for who they dated? It was funny being interviewed because I had to think really fast in order to find a way to tell some of the stories without going into detail about this guy or that guy. Some that is in the book though.

Q: You obviously covered a lot of ground, geographically and with Spitboy’s message in your music. Are there any specific memories that have stood out over the years?

Michelle: Really good or rowdy, memorable shows to stand out, but the things that stand out even more are the days when the camaraderie was really good. Like the time Karin and I bathed in Italian hot springs after our show in Rome; or drinking espresso made on the mini-stove in our tour van on a foggy cliff on the border of France and Spain, riding a ferry on the Sydney Harbor, and flipping off the dead presidents at Mount Rushmore.

Q: In retrospect, are you aware of the lives you may have changed through your music and lyrics?

Michelle: One of the things I have loved learning from people is that our songs, specifically the ones about gender, helped them better understand gender better, or their queer identities. A few gay men, and one or two trans folks, told me they were there rocking to Spitboy and songs like “What are Little Girls Made of?” or “In Tradition,” and choosing to reject what we now refer to as toxic masculinity or strict gender rules.

Q: You’ve always been adamant, both now and then, over separating the band from what was/is called Riot Grrrl. Can you explain why?

Michelle: Because we weren’t Riot Grrrls, and we didn’t want to be called girls or grrrls. Bay Area women in the 1990s, the ones I knew and hung out with, would correct anyone who called them a girl. There was a feminist bookstore near my house that went to a lot called Mama Bears, and they wanted be called womyn. We gotta reclaim that. I fucking hate writing the word women, seeing men in it, or son in person. I want to blow up all of those words. Grrrl doesn’t have man in it which is cool but there’s a whole other connotation with girl, the implication of youth, inexperience, etc. Grrrl is different; of course I get that, but regionally, it just didn’t work for us. Spitboy and Bikini Kill actually played together in LA, and when they came to town, we went to see them play, and Heavens To Betsy, and other Riot Grrrl bands. I remember things feeling pretty tense back stage, but then Mike D. from Beastie Boys showed up, and no one cared anymore.

Q: As someone who really got to know the bands’ music from “Body of Work”. I was wondering how you felt seeing/hearing the songs you were a huge part of creating, together for the first time.

Michelle: My honest reaction was, holy shit, Spitboy fucking holds up! The music doesn’t sound dated to me, and the musicianship is great. Together we created something really unique. Thinking back to all the guys in other bands who said, “oh, you guys have really improved,” makes it fairly clear to me that they said that bc we were women playing hardcore. Either they felt threatened or they saw women and heard women and not just Spitboy.

Q: How did the project come about and how hands on were you during the process?

Michelle: Joe from Don Giovanni reached out to the band a couple of years ago, and because we work by consensus with all five members (including both players, Paula and Dominique who succeeded her), and because were working on multiple time zones it took a long time to make all the decisions. Before that, we had to collect all the original tracks, have some tape digitized. One reel had to be baked, a special process that rids the tape from gumming which makes it unplayable. We made all the decisions about artwork, song order, and the rest of it together. I have the very long email threads to prove it.

Q: For those who have read or are looking to read “The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band.” What is the most important thing you’d want them to get out of it?

Michelle: Wow, that’s a great question. Honestly, two things. The first thing is that I wanted people to know me better. To know that I am a Xicana, and being POC in punk in the 1990s sometimes felt like a dirty trick. Us outcasts were attracted to punk because we were outcasts at least 2x over, but then you learn that punk is made up of people from the real world, punkers who will microagress you ten ways to Sunday. The second thing I was trying to do was to preserve the Spitboy legacy, to make sure people remember that Riot Grrrl wasn’t the only voice of feminism in punk.

Q: Women are often left out of conversation when it comes to the history of punk in general. I find it strange that I’m hearing of many female contributors for the first time more than forty years later. Why do you think this so and do you see things changing as time goes by?

Michelle: The simple answer is patriarchy. Why haven’t we had a womyn president? I have an essay coming that addresses this question more fully. It’s called the “Patriarchy of Punk.” It’s a response to Kevin Mattson’s 2020 book on punk during the Reagan Administration, We Not Here to Entertain. My writer friend, Ariel Gore was telling a story about a guy who cut in line at the bank, and she said (about that guy)“ Just because you don’t see old women, doesn’t mean we don’t exist.” A lot of men didn’t see women back then either, not unless they were adorned and fitting the expectations and standards of the male gaze. If they were some mousy girl behind a bass guitar, or the angry drummer, they weren’t seen and easily forgotten.

Q: What do think are some of the major misconceptions about Feminism? What do feel can be done to change them?

Michelle: That all feminists think the same way or that feminism is a White Womyn thing.

Q: Looking back, do you see your gravitation towards punk and hardcore any differently than you did then?

Michelle: I don’t really. I was an angry teen and a loudmouth. I hated Ronald Reagan, and had a lot of feelings early on about his policies, the misogyny, the classim, the war-mongering, and I had a lot of feelings about the way men leered at women, talked down to them, excluded them from conversations, and pretended we weren’t there.

Q: Do you feel that your experiences in a band and as a part of hardcore punk has influenced the way you teach or perhaps your socio political beliefs?

Michelle: Oh yeah, definitely, but I am a disciple of George Orwell, an anti-authoritarian, and I would never try to change someone’s beliefs. I don’t believe in that, but I don’t hide my beliefs either. I will push students to clean up any weak or lazy critical thinking.

Q: How, if at all has it affected your writing or perhaps the way you relate to people?

Michelle: People probably see me as immature for my age because I still consider myself a punkera, a menopunk now. Being in Spitboy, touring, and talking to people improved my social skills for sure. I was always the stand-offish one in the band, being the only person of color made it necessary for me to protect myself, but the other Spitwomyn came from pretty privileged backgrounds in communities where they learned good social skills and confidence. I learned a lot from them about how to use kindness to disarm people and how talking about issues that matter to us publicly really can give others the permission to do the same.

Q: A mutual friend told me your son is an accomplished pianist. Considering your and his passion for music. I couldn’t but ask, does that passion or talent run in the family?

Michelle: My son is a super talented and accomplished pianist. He plays jazz which he prefers to call Black American Music. My grandfather was a jazz/Latin jazz pianist and percussionist. He had a band that played parties, weddings, and quinceañeras in Los Angeles. My mom, who was the youngest, would get in trouble a lot, and when he'd have a gig, he'd take her with him to keep her out of more trouble, and make her play maracas or the guido. When my son was 1, I started taking him to kid music classes. I had a friend who lead this really good class where they sang songs in different languages and brought all kinds of cool instruments for the kids to play. I bought him a kid drum set too when he was 5 but he never really had an interest in playing the drums. He asked to play piano at 5 because of he really liked classical piano music and loved the Charlie Brown Christmas music by Vince Guraldi. We didn't have the money for a piano, so we kept putting him off. We relented at 7 and borrowed a keyboard. Now we have two pianos and multiple keyboards in the house. He plays jazz drums now too and a little bass and trumpet. He's a college student, and he works part-time for the Young Musicians Choral Orchestra, a program which supports student education and college endeavors by teaching them to play music and sing. He works in the office and teaches piano for them, and he gigs regularly with his own mates, but also often with professional musicians like Marcus Shelby.

|

|

|

|